During my second trip to northern Kenya in July 2021, I had the opportunity to observe the different styles of dwellings of the people we visited. What follows is not a rigorous study of the different dwellings throughout Kenya, but simply the informal observations that I had the opportunity to make during the trip that I led mainly through northern Kenya, including various tribes such as the Samburu, the Rendille, The Gabbra, the El Molo, the Turkana, the Dassanetch and the Yaaku. I have also added the Borana, Maasai and Pokot, from my first trip in March 2021.

During my second trip to northern Kenya in July 2021, I had the opportunity to observe the different styles of dwellings of the people we visited. What follows is not a rigorous study of the different dwellings throughout Kenya, but simply the informal observations that I had the opportunity to make during the trip that I led mainly through northern Kenya, including various tribes such as the Samburu, the Rendille, The Gabbra, the El Molo, the Turkana, the Dassanetch and the Yaaku. I have also added the Borana, Maasai and Pokot, from my first trip in March 2021.

For a not very experienced traveler, looking at the houses is perhaps not a priority, but when you share the afternoon with a local community and put your store next to their homes, you feel privileged to have the time to admire the diversity of the constructions and materials.

Most of the peoples we originally visited used to be nomads, and only recently can they be considered semi-nomads. However, this factor determines and is key to understanding how they build their houses. In order to reduce the overexploitation of pastures, the entire community will move after having been living in the same area for a certain time, and what causes this move is the shortage of pasture for their herds in the vicinity of where they have been living. This can happen around two or three months, but a community can also decide to stay longer because, for example, a well has been built, or because the government (which is very interested in these communities settling in) has built a school to help them settle. Therefore, it would not make much sense to build very elaborate houses or houses that are difficult to build, disassemble and transport.

We could therefore conclude that their way of living, closely linked to an economy based on herds and the priority of guaranteeing their subsistence, is what also marks the style of their houses.

Another factor that defines these buildings is the variety of materials used, since in most of the territory there are hardly any trees, a material that would be considered logical to use as raw material. Actually, considering natural materials available in these territories, such as rocks and stones, one would judge them as optimal for construction, but none of the traditional houses that we saw used this material.

A quick glance at these constructions would lead us to a too simple conclusion: "They are just huts", we would think. But the truth is that these houses differ considerably from one tribe to another, and they are all very skillfully built in accordance with the climatic conditions and the natural materials available to them.

Women, on the other hand, apart from taking care of many tasks such as taking care of children, cooking, fetching water and firewood, are also responsible for building and dismantling houses, while men are generally in charge of everything that concerns animals. The women help each other in the process of building, rehabilitating, dismantling houses, and organizing transportation. Donkeys, and also camels, are the preferred animals for transport, as they are smaller and can be easily carried, especially by a single woman. In this way, they can organize the load themselves and transport all their belongings to another place.

Also, as we are talking of rural communities sharing their habitat with wildlife, often a defensive fence is built around the area where the houses are. The fence is built using thorns and bushes and will be closed at night to protect the people and domestic animals from predators such as hyenas. Cattle, camels, goats and sheep will respectively sleep in separate enclosures in inner fences in the middle of the manyatta, which is the Swahili word for these fenced settlements.

When you enter one of these manyattas, you can see barefoot small kids running around, elders sitting on their wooden headrests under a tree, young girls holding a sibling on their backs, and women doing different chores. Young men are rarer to be seen, as they are the ones who take care of the herds and are away for the whole day. They will come home at sunset and will depart early the next morning. Or they might even spend the nights out with their cattle if the place is too far away to reach. Also, in the afternoon, you will see young girls with huge yellow plastic containers who are going to fetch some water. The well can be sometimes as far as three km away. Nevertheless, they hold the containers graciously on their heads, but more often, as they are so big, they have designed a smart pulling system with a wire, and so you can see what I call, “rolling water”. This will sure alleviate them, as the containers can be as heavy as 20 kilograms each, or more.

The Pokot near Lake Baringo

Although we didn’t visit this ethnic group in my second trip to Kenya, I would like to include it here, to have a wider picture of the different cultures of the area.

Near Churo, the houses are built by the women with reddish mud, and so they are permanent. They are more or less square with a pointed roof made of grass or a similar vegetable material.

Inside there is a single room with no divisions and very little furniture, but the majority of things, not many by the way, lay on the compact mud floor. The kitchen is outside, built with branches like a little hut with long legs. Why it is outside may obey a safety reason, in case of fire. There are also small huts to keep the chickens at night.

We also had the chance to visit another Pokot community. Their houses are round and not made of mud but of thin branches intertwined horizontally and vertically, with a single opening on one side and no windows.

The light filters from outside through the door and between the branches. Inside, the space is not very big and poorly furnished, with a fire pit almost in the way.

Most of the activities are carried outside. From dry branches of nearby small trees hang some kitchen utensils.

Here, there is no fence around the scattered houses but a separate round enclosure made of thorns and intertwined branches protects the goats.

The Samburu in Archers Post

These houses maintain a semispherical shape on the upper part, but they are rectangular and have a flat roof of different materials such as tarpaulin attached with ropes. They are not very tall. The entrance is through a single opening which sometimes can have a plank as a proper door. As you come inside, the whole place is surrounded in the darkness because there are no windows, but simple apertures between the branches with which the home is made. Little by little your eyes get used to the little light.

Inside, the place is divided according to the different uses: an area for cooking, with a little fire and some kitchen utensils. There is also a separate place for sleeping, generally on cow hides. There is no other furniture but the small wooden stools where they sit. Their belongings hang from hooks or lay on the bare floor.

The materials used for these houses are poles and tree branches and some kind of grass for the roof, which is sometimes also covered with tarpaulin attached with ropes.

The Samburu near South Horr

We spent the afternoon, the night and the next morning in this community, so we had plenty of time to explore the area and meet their inhabitants. They live in a huge manyatta, the enclosure made of thorns which is closed at night using a whole bush. Inside, the different homes are scattered leaving plenty of space among them, some of which is occupied by smaller enclosures for the goats and the camels at night.

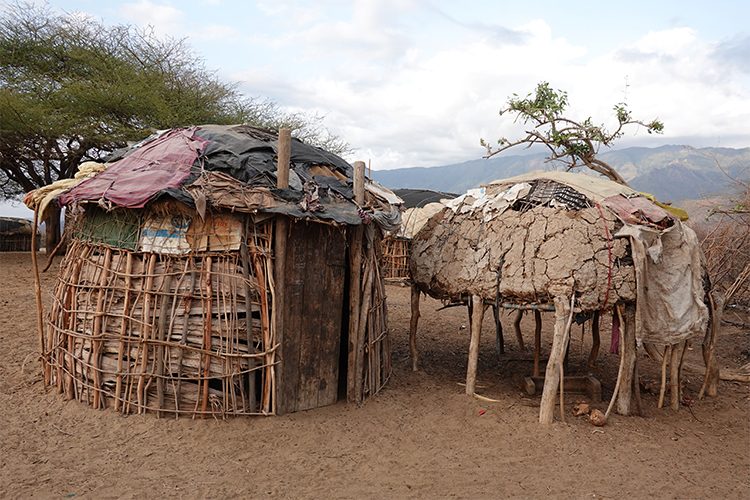

The houses are not very tall, and they are round and semispherical and made of vertical poles attached together with horizontal thinner poles. So, they form a checked pattern visible from outside, as only the top part is covered. The material used for this top varies from dried mud to fabric or a combination of both. Sometimes even plastic or cardboard attached in ropes are used. Some even had a mess of smaller branches.

Inside it is very cozy despite what you might think from outside. There is a little “hall” where the fire pit is placed and an area for the kitchen. Further inside, there is one single space for the whole family to sleep, generally on cow hides or mats. There are no windows but small holes in different parts of the walls.

As they are semi nomadic, once the pastures run out in the nearby areas, they will move on to a more proper area. The women, who together with the children and some elders occupy the place, tell me that the young men are with the goats and camels very far away. How far it is, is something I cannot determine, as we have very different conceptions of time and space.

The Turkana on the shores of Lake Turkana

This is a very iconic ethnic group. Their looks are haughty and show a very proud people. Their houses near the Lake Turkana are built in a very harsh terrain, and maybe this is what actually makes them the way they are. They used to depend on their cattle, which they hold in high esteem, and moved around freely looking for pastures. But pastures are becoming scarce and these pastoralist people have been forced to learn how to survive and adapt to the changes. Fish, once considered taboo for them, also for the Samburu, is now part of their staple diet.

Their houses look a bit provisional and humble. They are like small igloos made of dried branches and covered with all sort of materials, from plastics to fabric and nets. The interior is a bit messy and not very spacious.

The El Molo on the shores of Lake Turkana

This very small ethnic group on the shores of Lake Turkana near Loyiangalani have basically two settlements near Komote island. Their houses are rather different from the houses we have seen so far.

The main material used looks like dried interweaved palm leaves. Some of the houses have a corrugated aluminum sheet and a door, and the majority are square and not very tall.

They all lay scattered in a secluded area on the shore as they are not a dominant tribe which has been pushed away by others such the more dominant Turkana and Samburu. The village has no fence around and each house has its own small enclosure for the chicken. There are no other animals as the El Molo are not shepherds but they rely on the fish from the lake, which for them, contrary to other groups as the Turkana and Samburu, is not taboo. Also, they used to hunt hippos and crocodiles. Now, with the new laws protecting these beasts, can hunt them only occasionally, in special ceremonies.

The village has no proper streets but the houses are set on the pebbled shore in a not predetermined order.

The Dassanetch and their dwellings from Star Wars

The houses of this ethnic group near the Ethiopian border are unique in their style. Built using corrugated aluminum sheets all over, they certainly resemble the houses of the famous film. Scattered in a harsh area, the huge igloo-like structures shine in the sun, and seem pretty inconvenient under the torrid heat.

But as you step inside, they are ample and even comfortable, considering the little possessions one can find inside a house. At the entrance, there is a fire where they boil some tea which they kindly offer us, and the floor is covered in raffia mats. There are no windows and a thin smoke floats in the air.

The Dassanetch down the road

This community is very small, only one extended family, and they live south of Ileret, where we saw the huge dwellings of their neighbours made of corrugated aluminum sheets. The biggest area is occupied by the herds, three in total, belonging to the three families which make up this community. Once you enter the enclosure of thorns where the animals are, there is another barrier of bushes with an entrance which leads you to the area where three rather small and short huts are. The place looks a bit devastated and in worse conditions compared to the other ones we have seen so far. Maybe it is because this is truly a nomadic group which will not stay long in this place.

The materials used for building the houses are tarpaulin, plastics and sacks covering a fragile structure made of thin poles. Outside, long ropes make sure the whole structure does not blow away.

We put up the tents right outside the manyatta and count the endless hours without sleep listening to the bleat of the goats. In the morning, while the beasts responsible for our sleepless night stampeded outside the enclosure, I fold the tent and a scorpion runs away and hides among the thorns of the enclosure.

The Yaaku, the rock dwellers

Traditionally, the Yaaku were hunter-gatherers, which moved around in search of their prey and honey from wild bees, so they didn’t have a permanent constructed house, but took shelter in rock shelters in the Mukogodo Forest while they went hunting-gathering. They were considered darobo by their neighbours the Maasai, a negative word to designate those without cattle. Now, the pure Yaaku are a very small group and the majority are now mixed with the Maasai who have assimilated them. They build their manyattas outside the forest and have started to have their own animals too. They have even adopted the Maa language to the detriment of Yaakunte, their original language. It is said, that only a handful of elders can still communicate in Yaakunte.

The modern Maasai community in the outskirts of Nairobi

Traditionally, the Maasai used to live, and some still live, in bomas (another word for manyatta) and their houses are made of a mixture of cow dung, mud and wood.

But this is a modern community that we visited in the first trip in March 2021 and their houses are made of brick and are square, with a portico or veranda. Inside they are furnished with conventional modern furniture, with velvet sofas and flowery curtains. Despite the adaptation to modern changes, this community has maintained some of their traditional attire, and so they welcome us dressed in colourful robes, where red is the dominant colour, and the characteristic jewelery.

The Gabbra near the oasis in North Horr

This is also a seminomadic ethnic group, so their houses will be dismantled once the pastures around the area start to be so little that they pose a threat to the herds, mainly camels, and to their owners.

Women are again responsible for the constructing and dismantling, and also for the maintenance of the materials of construction.

We witnessed how a woman sat on the shade of her own house and very skillfully split apart the leaves of the palm tree which once dried will be used as a coverage for the roof.

Their houses are rather big and tall, semispherical and they look rather strong. They use poles as the main structure, but you hardly see them form outside, only in the bottom part. Then they cover them with colourful robes all around. Finally, the top part is covered with the dried leaves of the palm tree. The entrance to the house is a single entrance hole, rather narrow and covered with a robe that makes is quite difficult from the outside to distinguish from the other robes covering the sides. The interior is compartmentalized.

Here, there is no fence around the community and the houses are scattered in a harsh terrain only dotted with acacia trees and palm trees from time to time.

The houses in the sandy streets of North Horr are a combination of the houses in the previous description with other square mud houses with a thatched roof. Also, as it is a rather big town, there are other kinds of constructions, such as a catholic mission and a mosque, together with more simple buildings of corrugated aluminum sheet roofs, which work as shops and workshops.

The Borana near Marsabit

We had the chance to visit this community related to the Oromo in Ethiopia in March 2021. Their looks resemble those of their relatives in the neighbouring country: checked turbans for the men and long loosen and very colourful robes for the women. Their houses are permanent, as they are not nomadic and despite having cattle, they also cultivate.

This means that their houses won’t need to be dismantled, so the material used here is mud. The roof is of corrugated aluminum sheets.

The Rendille near Chalbi Desert

I loved the houses of this ethnic group so much! They are rather big and tall, of semispherical shape and they use all sort of colourful fabric in the outside, from traditional shukas (those fabric traditionally worn by the Maasai) to jean, T-shirts and jumpers attached graciously to the sides. The top part is made of a kind of thick dried grass and the walls are made of vertical poles.

The opening which serves as the entrance to the house is rather narrow and short, so you must enter sideways and bended.

Generally, a curtain hides this narrow passage to an interior which is spacious but again without any other opening, so your eyes need a certain time to get used to the darkness. The interior is divided in different areas to accommodate a different function.

The settlement we visited in the second trip in July 2021 forms a semi arch and the houses are organized following an order which represents the importance of the owner. Thus, there is the first house, occupied by the mother of the elder who takes us around. Then there is the second house, which is occupied by him and his family, as he is the first son. Then there is the third house aligned in the semi arch, in this case for the second son. And so, the whole place is organized following a patron of hierarchy.

ES

ES